A KIND OF LOVING (1962)

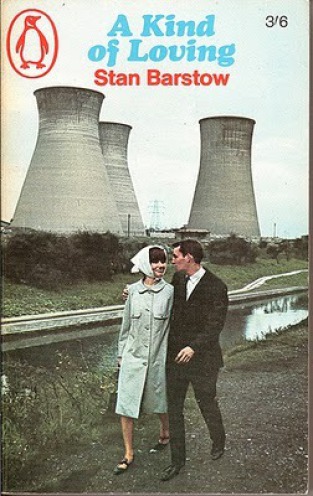

Based on the novel of the same name by Stan Barstow published in 1960

All page references to the novel are to the Parthian paperback edition reprinted 2017

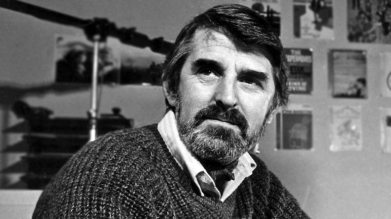

Stan Barstow's first novel was published in 1960, whereupon he was immediately classified as an Angry Young Man, although there is little anger and resentment in the novel or indeed in Barstow. However he does have a lot in common with other writers of the time - Northern, working class (alhtough much more of that anon), parochial (seen as a strength at the time, it is even now not meant as a pejorative term) - and as such his debut novel was a natural to be adapted into a film.

Room at the Top and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning had already been filmed, and before A Kind of Loving had been released it was beaten to it by A Taste of Honey, which came out seven months before in September 1961. Joseph Janni, whose biography deserves a page on its own (born in Milan during the Great War, he came to England in 1939 (good timing - he was brieflhy interned when Italy declared war on Britain!), bought the rights to the book and, after some bad experiences with Rank and British Lion, he took the project to Nat Cohen and Stuart Levy at Anglo-Amalgamated, with the proviso that John Schlesinger, then only known for his TV work, directed. The key involvement for me though was that two much sought after writers, Willis Hall and Keith Waterhouse, adapted the book for the screen. Hall and Waterhouse are two key, indeed giant figures in the cultural life of the time; Waterhouse had already written Billy Liar, which had then been co-produced for the stage with Hall, and the two - both from Leeds, whereas Barstow was from nearby Wakefield - set to work producing the script.

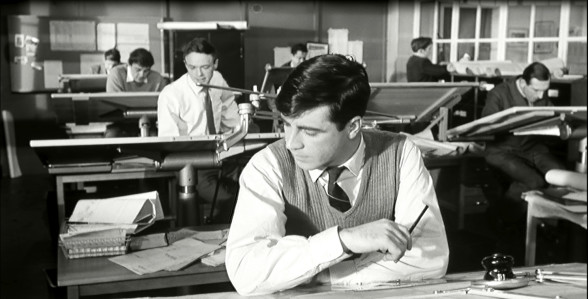

The book is clearly autobiographical. Barstow was born in Horbury in West Yorkshire, and was the son of a miner, leaving school at sixteen to work as a draughtsman in a local engineering firm. The book's narrator, Vic Brown, is from Cressley (believed to be Dewsbury) in Yorkshire, and is the son of a miner, and leaves school at sixteen to work as a draughtsman in a local engineering firm, Whittaker's....

Vic describes himself for our benefit near the start, mainly in terms of his physical appearance, but ends with:

So there I am - Victor Arthur Brown, twenty years old, one of the lads, and not very sure of himself under the cocky talk and dirty jokes and wisecracks. Take me or leave me, I'm all I''ve got. (page 25)

Although Alan Bates is great in the part, he was actually about 27 at the time the film was made, and is clearly too old to pass for 20, whilst Ingrid is only 18/19, with June Ritchie again slightly too old for the role at 23 or so.

The film stays very close to the book, not only in the story line (which is a pretty straightforward one anyway) but also to its spirit, in the sense of Vic's mindset and approach to life. The basic story is the most simplistic of all the New Wave films; Vic lusts after Ingrid Rothwell, who also works at Dawson's (changed from Whittaker's) but struggles to summon up the courage to ask her out (or indeed even speak to her). He can't make up his mind about her though, and comes across as rather callous (more so in the book) in his treatment of her, but decides it is a physical attraction only rather than a more mature relationship, and decides to end it. However, in a standard plot device of the time - many of the New Wave films rely on it - he finds out that Ingrid is pregnant, so the couple have to get married, which leads to Vic feeling trapped. After she has a miscarriage, and with Vic unsure what he wants to do, they decide to give it another go once they find somewhere to live away from Ingrid's mother.

Vic has a rather idealised view of women- he acknowledges to himself that he really wants to get married to a woman like his sister Chris (short for Christine), whom he is very close to and idolises. He therefore admires Ingrid from a distance, thinking about her - or rather his own idea of what he thinks she is like - all the time, despite never actually having spoken to her; but their first meeting, as described in the book, is faithfully filmed:

One thing the film adaptation does particularly well is subtly reproduce the vague hints and clues regarding the class situation of the couple and their family. Vic Brown is no Arthur Seaton, he has no grudge against the world, but nor does he want to necessarily 'get on' as such and disown his roots, like Joe Lampton in Room at the Top. He has clearly moved up the class scale in terms of his job - a white-collar worker, as opposed to his father (a miner in the book, a railwayman in the film) - and he finds himself drawn to aspects of 'highbrow' culture in the book (classical music, a Hemingway novel) but it is a more honest approach than Joe Lampton would affect (Vic doesn't hope to advance in any way from listening to classical music, he just finds himself liking it). Early on he notices a subtle difference between himself and Ingrid in terms of class:

We get to talking about our families because we don't really know much about each other, and I find out that Ingrid's Dad's a site engineer for a big constructional firm out Manchester way and his work takes him all over the country and sometimes abroad. 'He's really hardly ever at home,' Ingrid says. 'Mother says it's like being married to a sailor.' (I notice the way she says 'mother' and not 'my mother' or 'me mam', and this puts her family a notch above mine straight away.) (page 124)

It is of course the monstrous figure of Ingrid's mother, memorably played by Thora Hird, that dominates the second half of the film. Ingrid's father is dropped from the film (her mother appears to be a widow) which means that his conciliatory presence is missing, leaving Mrs Rothwell to completely rule the roost in what she persistenty reminds Vic is her house, where he must play by her rules. Apart from her general insufferability - I think she must have been the original template for all those tired old mother-in-law jokes - there is a class aspect to the mutual hostility, coupled with differing political viewpoints and outlooks. The class aspect is more explicit in the book, at their first meeting - at which Vic instantly dislikes Mrs Rothwell - it comes across more like an interview:

'How long have you known my daughter?' she says now, like a duchess asking a gardener for his references. I nearly expect her to say 'Brown', but she doesn't call me by any name all evening. (p260)

In the film Mrs Rothwell, when she first hears that Ingrid is going on a date with Vic, pulls a face when she hears he lives in Fountain Street (which is presumably in a poorer part of town), and asks immediately what his father does, when all Ingrid is doing is going on a first date with Vic, not eloping with him. Once they get married and move in, things soon start falling apart:

Although the sequence comes across as a bit clunky in its comparison of 'authentic' working class culture, represented by Vic's father and the brass band concert, with the false 'TV' culture being offered to the masses in the late 50s, it is actually pretty good shorthand for the contrasts that are frequently drawn in the book, where Vic often comments adversely on the new consumer culture:

'You like to read?' [David, Chris' husband]

'Oh, yes; I'm reading all the time. Beats television into a cocked hat, reading does.' (p119)

I take the book out of my pocket and hold it in my hands.

'It's For Whom the Bell Tolls. Have you read it?'

Good heavens, no, she says, she can't read books. She gets three magazines a week and can hardly get through them for watching telly. 'Telly.' I don't like that word somehow. It always reminds me of fat ignorant pigs of people swilling stout and cackling like hens at the sort of jokes they put on them coloured seaside postcards.....There's something just in the feel of a book, I always think; something solid that's here to stay. Not like television, switched on and off like a tap. I think it's a pity she doesn't read because it means we shan't ever be able to talk about the books we've both read and recommend them to one another. (p128)

These views were very common at the time, and are often reflected in the New Wave films; in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning for example, Arthur holds the TV in contempt, and is clearly disgusted with his father for being glued to it, whilst in The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner when Colin Smith's father dies a TV set is one of the first things his mother buys with the insurance payout. It was indeed the influence of the mass media and culture that led to Richard Hoggart writing 'The Uses of Literacy', published in 1957, which had a great influence in the development of media and cultural studies.

In the novel Vic works in a record shop in the town centre on Saturdays, and as he is made an offer by the owner, Mr Van Huyten, he eventually leaves Whittaker's and works at the shop full-time; this makes no difference at all to the story, and is dropped for the film, but it does mean that in the novel Vic is able to muse on teenagers buying the latest hits, which, like television, he views with something approaching contempt, and in fact it is through Mr Van Huyten that he slowly gains an appreciation of classical music and even goes to some concerts with his boss.

The book contains an interesting character, Conroy, who comes across as a complete 'Jack the Lad' tosser, foul-mouthed (by the standards of the day) and common, and he and Vic even have a fight in the office, which leads to Conroy deciding to leave the company. In the film he reappears by chance when he bumps into Vic, brooding on how things have turned out, in a pub, and they decide to go on a pub crawl. As Vic is not a drinker, he is soon very drunk. Conroy is played in the film by Jack Smethurst (later to find fame or notoriety in ITV's Love Thy Neighbour in the 1970s) but in the book he is a much more interesting character. Vic has marked down as a know-nothing common-as-muck oik, but he has to start rethinking his views as Conroy has an argument with a fellow employee called Rawly over Debussy, which he pronounces as Debewssy initially:

'Seems to me he got one up on you there,though, Conroy,' I say. 'About the violin concerto, I mean.'

Conroy's taking a long pull at his glass. He shakes his head as he puts it down. 'He didn't say it: she did. Shouldn''t be surprised if Rawly doesn't know Debussy from the Chancellor of the Exchequer.'

I notice now that Conroy pronounces the name like the blonde bit did and I begin to see that he was laying it on thick for Rawly's benefit. And I'm beginning to wonder if there isn't more to Conroy than meets the eye....

....Conroy's not letting talking stop him from drinkning and he's already emptied his first glass and started on the second.

'He [Rawly] buys The Times and the Guardian and the posh Sunday papers and reads all the critics and thinks that's it. He likes to blind you with a lot of names and facts. He can very likely tell you that Tolstoy had duck-egg and chips for his tea on 13 March 1888, but you ask him what they called Anna Karenina's fancy man and he'll look at you gone out.'

'Who's Anna Kar...what's her name?'

'Karenina. She's a woman in a book of that name.'

'How do you know?'

'Because I've read the bloody thing,' Conroy says; 'that's how I know...What''s up? - surprised? Thought Reveille was my steady diet, did you?' (p177-178)

This, understandably, is all dropped in the film, and it is another friend, Percy, that he goes on a bender with; either way, in both book and film, he ends up back at his mother-in-law's house to a frosty welcome:

Vic finds that he gets short shrift from not only his beloved sister Chris, but also from his mother; he at last begins to realise that he is the selfish one, not Ingrid, and it's up to him to make the most of the situation. Actually it is the film that has, for me, the better ending, as in the novel by pure chance one of Chris and David's neignbours is about to go to Canada and the flat is up for rent, which is really all too convenient (and reminds me a bit of a similar plot device at the end of The Family Way) whereas the film does not have any such easy option. In the novel it is Ingrid's father who helps Vic see sense, and Vic sums up the situation to himself at the end:

Walking back to Chris's I turn it all over in my mind. She still loves me. After all that's happened - the way I mucked her about, the accident and losing the baby, the way her mother's tried to turn her against me, and the way I've behaved - after all that she still loves me and she's ready to try and make a go of it. Whether I love her or not's another thing altogether, but that's not what matters now. What matters is I know I'm doing the right thing. I'm tired of feeling like a louse and now I'm going to go the best I can. And who knows, one day it might happen like Chris said: we might find a kind of loving to carry us through. I hope so because it's for a long, long time.

(p 344)

The film ends, for me, on a similar, but slightly more positive note, as the couple face up to their responsibilities:

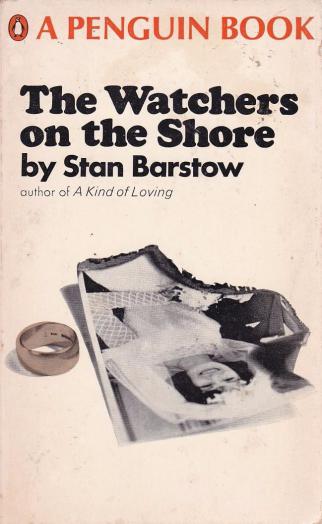

It's one of those films where I wonder what would really become of such a couple; unfortunately I can't help thinking that they would end up divorcing, they have very little in common and I think it would be hard to overcome her dreadful mother and the circumstances in which they first got married. But I've just discovered that I can now find out exactly what happened to the couple, as Barstow wrote two sequels, known as the Vic Brown trilogy, with The Watchers on the Shore published in 1966 and then The Right True End 10 years later in 1976, so I've just bought The Watchers on the Shore and it should be delivered early next week I hope.

A Kind of Loving can be bought in a new edition for about £8-£9, or second hand from somewhere like www.abebooks.co.uk for only £2 or so.

The DVD seems to be around £6-£10 at the moment (or I've just seen it on ebay second hand for £1) or it will set you back about £14 or so on Blu Ray if that's your thing.

The more I watch the film the more I think a case can be put forward for it being the best of the New Wave films, and the book is equally enjoyable, and for once it is a very honest and straightforward adaptation.