THE SERVANT (1963)

From Robin Maugham's 1948 novella

The Servant, directed by Jospeh Losey and scripted by Harold Pinter (his first screenplay), is one of the most famous British films of the 60s. It provided Dirk Bogarde with one of his most celebrated and memorable roles as Barrett, the manipulative manservant.

The novella (75 short pages) is much less known; it was published in 1948, written by Robin Maugham (nephew of W. Somerset), later 2nd Viscount Maugham.

As is often the case, the book is now published with a film still, (see my copy published in 2000, right), emphasising that the film version is much better known. My edition has an introduction by Neil Bartlett, which throws some light on Maugham's life and the autobiographical elements in the novella.

The missing narrator

The novella is so short, it is little more than the outlines of a tale - more of a fable really. The first surprising thing on reading it if, as usually happens, one knows the film very well before reading the book, is that it is narrated in the first person by a Richard Merton, a publisher, who knew Tony in the war (the book is set in 1946-1947 I think). He gains his insight into the situation with Barrett, when not from personal observation, from Sally Grant (who becomes Susan Stewart, played by Wendy Craig, in the film), Tony's girlfriend, and, in one key scene, from Tony himself.

Taking out the narrator means that we, the audience, tend to put ourselves in the place of the narrator, but in this instance, to a large extent, Susan takes up the narrator's perspective, and we see many of the early scenes through Susan's eyes.

In the book the narrator meets Barrett in chapter 2:

He was over six foot...His shoulders were narrow, and his hands were long and bony...in the middle of his sallow face were stuck a pair of rosebud lips, which gave him the look of a dissolute cherub. His lids were heavy and looked oily, I remember.

Six months pass before the start of the next chapter, whilst Merton has been in the Middle East. He sees a difference in Tony ('He had put on weight, and there was a coarse look about him which I had never seen before.') before running into Sally, who wants to talk to him about Tony and Barrett. She confesses that she detests Barrett, and describes how there was a battle of wills between her and Barrett over some lupins that she had brought round.

Vera and Barrett

The next chapter is strange in that most of it is nothing to do with Barrett and Tony (it mainly involves the narrator and his housekeeper discussing whether to go and get some ice or not) which is odd given that the book is so short anyway. The only relevance in the sense of the film's narrative is that Vera is mentioned for the first time, although in the novella she is supposedly Barrett's niece, whereas of course in the film, as played by Sarah Miles (left), she is allegedly Barrett's 16 year old sister. It is also mentioned by Tony that he hasn't seen Sally for a while.

In the next chapter the narrator and Tony meet at a regimental reunion dinner, and they walk home, but Richard goes home and doesn't go into the house with Tony.

Six months later Tony told me what happened that night. I give his account here in order to preserve the sequence of events.

The scene where Vera seduces Tony is then relayed. What is very noticeable is that the narrative order has changed; in the film, the scene where Vera arrives by train is intercut with Tony and Susan in a restaurant (of which more later), but although Vera is supposed to be Barrett's sister, it is immediately clear that this is not in fact their actual relationship (they are not related and are in a sexual relationship instead) before Vera seduces Tony. The following short clip makes it clear to us, the audience, that Tony is being deceived:

The scene itself however is perhaps the only scene that Pinter has more or less lifted from the book, including the dripping tap:

He felt he had lost control of reality. The plates on the dresser and the two cups on the sideboard seemed part of another world. A tap was dripping into the sink. Each drop fell at regular intervals like the beat of a metronome. He was breathing heavily. It worried him that his breath did not keep time with the drips. He could hear the two sounds cutting across the stillness of the room.

This is brilliantly realised in the film, the drip from the tap increasing the sexual tension between the pair.

Lost and found scenes

Part of the social background? Pinter pours the wine (far left), Tony and Susan in the middle background

Part of the social background? Pinter pours the wine (far left), Tony and Susan in the middle background

There are two main scenes in the film that are not in the book; one is the scene at lunchtime in a restaurant, which picks up on three different conversations (including Patrick Magee and Alun Owen as bishop and curate, and Harold Pinter with a woman). This was obviously a key scene for Losey; in Alexander Walker's book 'Hollywood England' he quotes Losey as saying:

"The little vignettes in the restaurant were all written during shooting ... I called Harold and asked him to write me some little bits to go into the restaurant scene and he asked what and I said, "Two lesbians, a bishop and a curate, a society girl and her escort." So he wrote them overnight and I had them in the mail the next day ... They were part of the background of the characters and the social background of the whole film."

On the other hand I have always found this scene completely superfluous and regarded it as adding nothing to the story or even the atmosphere. Likewise, there is a scene with Susan's parents where there is a mildly amusing mix-up over gauchos and ponchos, but again I feel that this is just padding the film out unnecessarily.

So much has been written about The Servant in glowing terms, that I almost denied the feeling in myself that despite some of the brilliance of Pinter's writing, and Bogarde's extraordinary performance, the film as a whole was overrated and certainly was not part of the zeitgeist of the Profumo affair etc (although to be fair to Losey and Pinter, they never claimed it was and of course the film was made before this affair hit the headlines).

Disjointed narrative

It was therefore refreshing to see what Robert Murphy had to say about it in this key book 'British Sixties Cinema', and see that he too is not really a fan. Whilst admitting that:

" The Servant is a cold, clever film which leaves an indelibe impression"

he goes on to argue that:

"Underneath this brilliant surface, though, there are serious flaws. Harold Pinter's script strains for effect and makes nonsense of an already weak story ... it is difficult now to see anything more than fortunate timing and a vague air of decadence linking this muddled upper-class nightmare to the real-life scandal of the Profumo Affair which boosted its office box-office potential."

I would largely agree with that, particularly the point about a weak story. As has already been described, the book is so short and sketchy that Pinter must have had a field day, as there was very little dialogue or plot points that he needed to adhere to, and some of the exchanges are therefore pure Pinter. I studied Pinter for 'A' level, so know plays like 'The Caretaker' and 'The Birthday Party' extremely well - a couple of lines which always stuck in my mind feature in the scene where Susan berates Barrett to see if she gets a reaction, and asks him:

'Do you use a deoderant?'

before the classically Pinteresque:

'Do you think you go well with the colour scheme?'

Again, this scene is not in the book.

It is actually at this point in the film where there is a lack of continuity and a 'flow' to the story. I wouldn't go as far as Robert Muprhy in calling it 'nonsense', but somewhere along the line Pinter (and Losey) seem to sacrifice narrative sense for effect. For instance, in the scene described above, Susan has already drifted out of the film, and Tony's life, to some extent (she does not feature for nearly 25 minutes). Yet, after Tony begins sleeping with Vera, she abruptly comes round and starts ordering Barrett about. There is no comparable sequence of events in the book, which makes me wonder why Pinter wrote the script in this disjointed manner.

In the novella the parting of the ways of Sally and Tony is more sensibly handled; she simply gets fed up wtih Tony being in thrall to Barrett, and the narrator finds out in a chapter based largely on letters he receives whilst in New York that Sally has married someone else and moved to Rhodesia with him.

Of course in the film this is, understandably, handled more dramatically; in the novel it is Merton who, looking after the house whilst Tony is away, finds Barrett and Vera in bed together, whilst in the film it is instead Susan and Tony together who discover the true nature of Barrett and Vera's relationsip, and Vera's remarks make it obvious to Susan that Tony has been sleeping with her. Susan leaves, and does not return until the end of the film.

Another big jolt for me is the too-sudden role reversal after Barrett meets Tony in a pub and apologises to him, blaming everything on Vera and asking to be forgiven and given his old job back. This is taken direct from the book, even down to Vera supposedly having run off with a bookie. In the book this is all relayed to Merton by Tony in a letter, with Merton in New York replying sarcastically, that:

"I rode on a dromedary from New York to San Francisco in seven hours ... This morning I was elected President of the United States. I reckon you will believe all this, because if you believe Barrett's story you'll believe anything. Love, Richard."

The problem now is that, in the book, the narrator does not return to England for about a year, and admits that:

"I am unable to explain the reason for the increase in Barrett's influence during the year I was away"

and goes on to admit that:

"I expect he took on his role of dragoman step by step, with sly little hints and furtive allusions..."

Unfortunately the film jettisons this subtle approach, and we cut immediately from Barrett apologising in the pub, to the scene below, where the relationship between him and Tony has been radically transformed:

Ending - book

The ending of the film is, for me, where the real problems lie with the film version. The film starts to slide, in my view, about 20 mins from the end, when Vera suddenly turns up at the house, asking to speak to Tony. She wants money, and professes that she loves him, and Tony is weak enough to believe this before Barrett drags her out, although when the camera stays on them in the hallway it is confirmed for us that they are still playing games and that it was all planned.

Crucially there is a scene in the novella involving the narrator that has been completely removed from the film version, which drastically changes the ending and its meaning. This comes in the penultimate chapter, where Richard ends up in Piccadilly on a bitterly cold night, trying to get home. He sees a prostitute accosting would-be clients, only to realise that it's Vera. The story of her running off to marry a bookie turns out to be completely false, and Richard goes back to her flat to hear her story (yeah, that's what they all say mate). Vera's version is that Barrett got rid of her after he was sacked by Tony:

'He chucked me. That's what happened. He'd found another girl, see. He only likes them young.'

Richard then has to eventually 'make his excuses and leave', as the saying goes. When he sees Tony and Barrett the next evening, he tricks Barrett into confirming that he is lying about Vera, but they are then joined by someone:

In the stillness we both heard the key turn in the lock of the back door. Someone was coming in. The door opened, and a young girl pranced into the kitchen. Her face wqs inexpertly rouged, and her waist and emaciated hands were tiny. She looked like a child dressed up in her mother's clothes.

Merton tries to get Tony out of Barrett's grasp:

'Come with me.'

He stood swaying on his feet, staring at me.

Barrett's high-pitched voice broke the silence.

'We're waiting for you, Tony,' he called out. 'We're both waiting for you.'

There was a furtive giggle, then a little gasp, a whimper, then silence. Tony flushed. He began to tremble all over.

'Come with me,' I urged.

But he was no longer listening. He was breathing heavily, and his eyes were dilated. Then he broke away from me with a low cry and stumbled towards the kitchen door.

'I'm staying,' I heard him say in a thick voice. The he turned round, For a moment our eyes met.

'Goodbye, Richard,' he said. 'Have a good time in prig's alley.'

'Goodbye, Tony.'

I opened the door and walked out in the cold darkness. The fog was so thick that sometimes I would get lost in stretches of deep blackness between the circles of light from the lamp-posts. I knew it would be a long journey before I reached home.

Ending - film

Obviously Pinter and Losey have abandoned this ending completely, and opted for the famous/infamous party/orgy ending. I was never very keen on this ending, and now that I have watched it yet again in preparation for this page, I realise that it actually makes no sense whatsoever.

Firstly, because the narrator has been removed, the script needs an 'in' to the party, which is provided by Susan (in the book of course Sally has long since gone off to Rhodesia). However there is no reason for Susan to return; in fact when she turns up she mumbles something to Tony: "Vera's been to see me. She says you owe her some money" but this would be highly unlikely, and even Tony, in his drunken/drugged stupor realises this, saying "You didn't come here because of Vera!" It is even more implausible that Vera is actually present at the party, combing her hair in the bedroom!

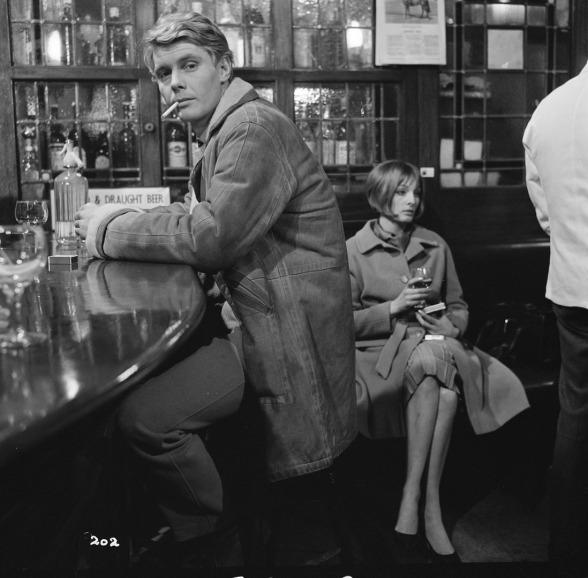

The other three women there also remain largely unexplained, particularly one woman ('Girl in Pub, played by Alison Seebohm, according to the credits) who sits silently in the corner; she appeared once before in the film, in the pub (above), where again she sat silently staring at Tony who simply stared back. Here is the ending of the film in full:

The whole film does not seem to be available to view on youtube, and the DVD now costs over £10 (I have an old copy, I think it cost about £6-£7) but there is also a 50th anniversary edition out featuring interviews with Sarah Miles, Wendy Craig etc which looks good value. it can also be bought now on Blu-Ray as well if that's your thing.

The book now also seems hard to buy cheap, I can't find it at abebooks for less than £8 (unless you can read French) and I'm sure I didn't pay anything like that for it when I got my copy a couple of years ago.

For real fans of the film it would be worth hunting out a second-hand copy of the book and comparing the two, I'd like to know what people think.

[Stop press June 2013]: I've just got hold of a book about Harold Pinter's work for the screen by Steven H Gale called 'Sharp Cut: Harold Pinter's screenplays and the artistic process' (Pinter's screenplays have always interested me, and in any case I've always been of the view that the script is far more important than the director). Just read the chapter on The Servant, and was pleased to see that a lot of what Gale says is noted above, as I came to the conclusions independently. The chapter could have done with a lot more exposition regarding the ending though, as it is so different from the novella.