KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS (1949)

From the novel 'Israel Rank' by Roy Horniman published in 1907

All page references are to the Chatto and Windus edition of 1907, republished a few years ago

This most famous of British films - coming 6th in the 1999 BFI list of best British films of the 20th century - has rather less famous antecedents, as the novel on which it is based, Israel Rank by the unknown Roy Horniman, is one that very few people have ever heard of, let alone read.

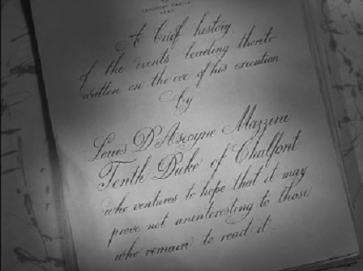

A few years ago I decided to add myself to the list of its readers, and since then I wanted to write a piece on the adaptation, but as usual laziness etc got in the way, until now. Subtitled 'The Autobiography of a Criminal', it is impossible to read now without seeing Dennis Price, or Joan Greenwood as Sibella, or Alec Guinness in eight roles (wikipedia and the BFI say nine roles, but I don't think that's right) as the D'Ascoyne family; indeed it is hard to imagine anyone who has read the book but not seen the film. As the film is particularly feted for its script, I was intrigued as to why the novel was so little known, although it is often the case that the better a book the worse the film, and vice versa, although it is certainly not true to say that the book is a poor one; far from it, although I will say at the outset that the script and subsequent filming is superior in every way to the novel in my view, for reasons which I will detail.

It is worth pointing out that, whilst retaining the wit and elegance of the first person narration in the form of a voiceover, hardly any of the original prose or dialogue is used in the film, although clearly the narrator's style appealed to the director and co-writer Robert Hamer, who famously said at the time:

What were the possibilities which thus presented themselves? Firstly, that of making a film not noticeably similar to any previously made in the English language. Secondly, that of using this English language, which I love, in a more varied and, to me, more interesting way than I had previously had the chance of doing in a film. Thirdly, that of making a picture which paid no regard whatever to established, though not practised, moral convention. This last was not from any desire to shock, but from an impulse to escape the somewhat inflexible and unshaded characterisation which convention tends to enforce in scripts. (quoted in Newton, 2003, p7)

There are numerous examples of where the style of the book's narrator is imitated but not copied, but my favourite comes as Louis tours Chalfont Castle as a paying day tripper:

There were then some eight people between me and the Dukedom, all seemingly equally out of reach; it is so difficult to make a neat job of killing people with whom one is not on friendly terms.

Basic changes

There are of course a few basic changes, and then some very key changes to the narrative, if not characterisation, to the novel in its process to the screen. The novel is in the first person, easily mirrored in the film by a voiceover, one of the most memorable first person narrations in cinema. In the novel the main character is, as one might suspect from the title, Israel Rank, although his full name is Israel Gascoyne Rank (the family are called Gascoyne in the book), who is half-Jewish (English mother, Jewish father), which leads to many discourses throughout the book on the nature of the Jewish race, and which allows the Gascoyne family members (or some of them anyway) along with general society to act in a prejudicial way towards Rank, above and beyond the class element. Robert Hamer and John Dighton, who wrote the screenplay, wisely sidestep this potential can of worms by making the main character half-Italian instead and calling him Louis Mazzini. I say wisely because at the time - remember this was ony four years after the war and the Holocaust - this was a very sensitive subject (as indeed it is now, at the end of 2019) but in particular the topic had arisen a year before. David Lean had made Oliver Twist, released in 1948, but the film had received a great deal of criticism for its portrayal of Fagin, especially Alec Guinness' prosthetic nose (and of course Guinness features prominently in Kind Hearts and Coronets) which led, in America,to cuts and bans. It is not hard to imagine that Ealing Studios, and Michael Balcon, wanted to avoid such a controversy (Balcon was uneasy enough about the film as it was, given that it was a black comedy entirely at odds in terms of approach and tone to the rest of Ealing's output).

A few other changes were made, none of any great import; in the book Rank's father dies when he is 7, in the film he dies immediately his son is born, in the book the family's lodger, a long time admirer of Mrs Gascoyne, leaves them some money, in the film the lodger finds Mazzini a job but performs no other function, in the book Rank aspires to an Earldom whereas in the film he goes one higher and hopes for a Dukedom, and so forth. There are also a number of other characters who float in and out of the book - Lady Pebworth, who introduces Rank to high society, Sir Anthony Cross who is fixated with Sibella etc, but they can all be safely excised from the film without altering the story or its tone in any way.

Motivation

In the book Israel Rank is quite snobbish (as he is in the film) and alive to the intricate layers of class and etiquette of the time, and from an early age he is conscious of the gulf between his current circumstances and that of the aristocratic family of which he is a distant member:

My mother married beneath her....They were not rich but they were gentlefolk, and by descent something more. In fact only nine lives stood between my mother's brother and one of the most ancient peerages in the United Kingdom. (p 8)

He starts studying the family tree in his teens (even reproducing it on page 18) but gets into bother at school when he unwisely boasts of his ancestry during an argument:

My distant relationship to the Gascoynes was the cause of some humiliation at school. There was a boy whose father has just been made an Alderman of the City of London, and he was rather boastful of the fact.

"Bah! what's an Alderman?" I asked.

Instinctively the other boys felt that it was not right that one of Hebraic extraction should make such a remark. They had the intuition of their race that a Jew is after all a Jew....

[After insults are thrown at him, including by Lionel Holland]

"If six people were to die I should be Earl Gascoyne," I said grandly.

There arose a shout of laughter.

"Pigs might fly," said Lionel Holland. (p 19-20 - in the film this last line is given to Sibella)

Israel writes to one of the Gascoynes (Gascoyne Gascoyne, great name), the head of a stockbroking firm, but a letter comes back typed by a secretary snubbing him, and it is only after the death of his son (caused of course by Israel) that he relents. After the death of his mother Israel drifts aimlessly, resigning from what he regards as his menial job (as a banker's clerk, not a draper as in the film) and squandering what little money he has been left; however crucially there is no mention of his mother's funeral and burial, and he certainly never writes to the family asking for her to be buried in the family vault. His motive for his serial killing career stems entirely from a fear of poverty - which he calls the greatest evil - and from a skewed sense of justice ie that the Earldom rightfully belongs to him. In the film care is taken to provide Louis with a stronger sense of righteousness and a burning desire for bitter revenge on behalf of his mother:

Who does Rank/Mazzini kill?

It's worth going through the sequence of deaths and killings to see where the film has made certain changes:

| Book | Film | |

| 1st death | Gascoyne Gascoyne, son of a banker. He goes to a hotel in a small village, Lowhaven, and Rank poisons him and the woman he is with, so two deaths take place. |

Henry D'Ascoyne, with a woman, is killed by Mazzini as he lets their punt loose and it goes over the weir. Although the method is very different, again two deaths take place. |

| 2nd death | Henry Gascoyne (whose sister is Edith Gascoyne, whom Rank later marries) is seeing a woman, not of his class, in the village. Rank writes an anonymous letter to her father and brothers, and as anticipated he is badly beaten. By chance Rank finds him by the roadside and strangles him to finish him off. |

In the book the method is entirely different; Edith is married to Henry, not his sister, and Mazzini finds that Henry is very interested in photography and takes up the hobby to get near to him. He kills him by the ingenious method of substituting petrol for paraffin in the dark room lamp; Henry is killed in the explosion some hours later. |

| 3rd death | Rank befriends Ughtred Gascoyne, a 55 year old bachelor; Ughtred however has a lady friend and Rank worries that he might marry her and start a family. He commits arson at Ughtred's flat one night. | No equivalent (there is no such character in the film) |

| 4th death | Reverend Henry Gascoyne is a vicar in Lincolnshire, Rank poisons him but gets it wrong first time round and the verger is killed instead, so causes two deaths. | As in the book, Mazzini poisons the reverend but in order to do so makes his acquaintence, whereas in the book Rank deliberately never meets his victim. |

|

5th death |

No equivalent (there is no such character in the book) |

Lady Agatha D'Ascoyne is shot down from her hot air balloon. |

| 6th death | No equivalent (there is no such character in the book) | Lord Admiral Horatio D'Ascoyne goes down with his ship, but Mazzini plays no part in his demise. |

| 7th death | No equivalent (there is no such character in the book) | Lord General Rufus D'Ascoyne is killed by a home made bomb made by Mazzini. |

| 8th death | Earl Gascoyne has a wife and baby son, Lord Hammerton; Rank insinuates himself and manages to become a regular visitor at the ancestral home, Hammerton. There is a child there, Walter Chard, who has been taken in by the family and who has a governess. Walter catches scarlet fever, and Rank manages to get hold of the child's infected handerkerchief and lets the baby play with it, thereby catching the fever himself and dying from it (although Walter survives) | No equivalent (the Duke is childless) |

| 9th death | Rank poisons the Earl but he, by his own admittance, makes a mistake and it is too obvious, and he is arrested and convicted | Mazzini arranges for the Duke to be caught by his own trap whilst out hunting and shoots him in cold blood, making it look like an accident. |

In the book therefore Rank is directly responsible for 8 deaths, including an infant, with two of the deaths 'collateral damage' as one might say; in the film Mazzini is responsible for 7 deaths, one of which is accidental in a sense. However it is the manner of the deaths which in almost every case is completely different and overall, much cleverer and more 'amusing' in the film than in the book. Three of the D'Ascoyne family - Agatha, Horatio and Rufus - are dreamed up by Hamer and Dighton, and despatched in swift, comedic succession (although Horatio does not die at Louis' hand) and noticeably the deliberate killing of an infant is removed from the film (it would presumably not have been possible to film at the time, and Louis would have lost all audience sympathy). The only murder in the film which is possibly misjudged is the final one, that of the Duke, who is shot in cold blood at close range; not only that, Louis goes out of his way - and possibly risk being caught - to tell the Duke what he has done and is about to do, unlike any of the other murders.

Nevertheless I have always admired the following scene (not in the book, he does not attend Henry's funeral) which manages to introduce, in an entirely cinematic and engaging way, the whole family, including of course the Rev Henry, "talking interminable nonsense":

Esther Lane and Lionel Holland

The most radical and interesting changes are those made to the characters of Esther Lane and Lionel Holland in the change from book to film. If those who know the film well are confused at this point, wondering who Esther Lane is, don't be; she has been dropped from the film, but plays a key role in the latter sections of the book. As Israel hones in on his goal, he becomes a regular visitor to the ancestral home of the Earl, Hammerton (Chalfont Castle in the film), whilst his fiancee Edith is in the South of France for a few months prior to their wedding. There he meets Esther Lane, who is the governess to a child, Walter Chard, who is the orphan son of an old friend of Lady Gascoyne. He falls in love with Miss Lane almost immediately, and his feelings are reciprocated. He plays matters very coolly however, as he is (a) about to be married to Edith and (b) there is always Sibella, so the last thing he needs is another entanglement. The problem is that it becomes clear, once the book is read (see below for the final twist in the book) that she is merely a device to get hm off the hook, and although this is clever in a way it is rather clumsy in other respects and doesn't quite come off.

Lionel Holland of course appears in both book and film, but his character is used far more effectively in the film, as will be seen. The book actually paints a far more detailed picture of him in the first half at least, as he and Rank have a natural animosity towards each other and on one occasion Holland goes out of his way to poison the company against him, pointing out his lowly origins to all and thereby damaging Israel's attempts to ingratiate himself into society. He is also of course a natural enemy to Israel as he marries Sibella (Joan Greenwood's playing of the character is quite perfect), although Israel has some form of revenge on him as - if I read it right - he sleeps with her on the night before her marriage. In the book Israel is left alone with Sibella as her brother Grahame goes off somewhere for a short while:

Her mouth had always been to my mind her chief charm, and when I found my lips pressed against its large, sweet lines...I lost my head - that is, if I had had any desire to keep it.

Old Mr. and Mrs. Hallward dozed away in their armchairs by the drawing-room fire....I have no doubt the house outside looked just as respectable and unemotional to Grahame when he returned to it as when he went out of it, but, all the same, I was wondering when he rejoined us if Sibella would think it necessary to break off her marriage at the last moment rather than marry a man she had betrayed. (p 189)

Now I remember reading Tess of the D'Urbervilles at school (in the days before the National Curriculum schools had a lot of freedom to choose their own texts for O levels etc, and our English teacher Mr Palmer, being a member of the Thomas Hardy Appreciation Society, seized his opportunity to feed us as much Hardy as he could get away with) and not realising what had happened in the scene where she is effectively raped by Alec D'Urberville; it was only when she gives birth the following year that I had to go back over the book to see what had happened. Since then I have been more attuned to such scenes, and in the film it is equally subtle, as Louis comments to Lionel, the day after he seduces her: "You're a lucky man Lionel - take my word for it."

As the book goes on Lionel falls away as a character, and plays almost no part in the latter parts of the novel, but this is where Hamer and Dighton produce a stroke of genius; rather than have Louis get caught in an amateurish fashion, why not have him arrested for a crime he didn't commit? In an audacious and brilliant move, they use the character's supposed suicide - more on that in a moment - to provide circumstantial evidence of Louis' supposed guilt, setting it all up with this scene:

It is then Sibella's evidence at the trial that condemns Louis to a guilty verdict, but watching it again one odd thing struck me, which is that she says on oath that she went back to their apartment and found Lionel "with a dagger stuck in his chest". It later becomes clear that Lionel had written a suicide note, and Sibella had taken it, intending to use it as a lever to blackmail Louis whilst saving him from the gallows. However, I now question this; killing oneself with a dagger through the heart is a very strange way to commit suicide; it seems much more likely that Lionel would have used poison, or shot himself if he had access to a gun. I now lean towards the view that Sibella found Lionel in a drunken stupor, saw the suicide note, which he had probably thought better of by then anyway, and stabbed him herself, all so that she could exert influence on Louis (she already suspects that he has killed some, if not all of the D'Ascoyne family).

The ending

By this stage book and film have long since parted company, but each of course must follow the logic of its own narrative through. However, whilst the former ends without ambiguity, having set up its 'surprise' ending, the film ends with one of my favourite devices, the 'open' ending where the viewer can draw their own conclusions.

In the book, Esther Lane plays out her function in order that Louis can escape hanging; she commits suicide, leaving a note confessing to killing the Earl (because he had compromised her in a relationship). Louis is therefore free, and the novel ends rather tamely:

But to this day, there is a sadness in my wife's manner, and although she tries to hide a shuddering aversion to me when we are alone, it shows itself unexpectedly in trifles. In some way she has grasped the truth. Indeed, she must have done, for there can be no other explanation of her conduct. We have two children, and perhaps there is something pathetic in the amount of moral training she gives them. I am sure there is no need for Hammerton to turn out other than well. I have done the work. He has only to reap the benefit and the reward. The second boy is a gentle little creature, Oriental in his nature, and most devoted to his father, as they both are, but the second boy especially so.

Sibella is still - Sibella. (p 408)

Hamer and Dighton obviously have to come up with a completely fresh ending, but they have prepared for this by opting to use the Lionel Holland character as detailed above. Sibella, whose false evidence has condemnded Louis, now goes to him, spelling out (albeit in beautifully couched terms) that she can produce Lionel's suicide note, but in return...well, what? Louis is in no doubt that Sibella's demand will be that he kills Edith, but I've never been quite so sure, although watching it yet again maybe it's me that's slow on the uptake, but judge for yourselves:

The suicide note is produced at the last minute - "how very like Sibella", Louis ponders - and he leaves a free man, with both Edith and Sibella waiting for him (although in reality it would be absurd for Sibella to be there). The brilliant final moment then appears; what about his memoirs, where he has recorded all his murders? The book covers this aspect quite neatly, as the prison governor tells him that he will shortly be released:

Then I recollected my manuscript on the table. No one had seen it but myself, but if it were noticed it would be awkward.

it was a terrible moment. I expected the Governor as I picked it up to say: "Anything written in a prison becomes the property of the Crown," but I was allowed to walk off with it. (p 407)

In the film of course, we are left to wonder for ourselves, as Louis, approached by a representative of Titbits magazine (Arthur Lowe in an early cameo) for the publication rights of his memoirs, realises that in all the excitement he has left his memoirs behind, leaving the question: is he to be found out at the last moment? I've no idea if the working script gives any clues, but my own thoughts are that he simply goes back to the gate, asks to see the governor, and is simply allowed to retrieve the manuscript without further ado (he is a Duke after all, and the governor throughout has been most obsequious towards him). At that time films were not allowed to show crime being rewarded, so by this method Hamer and Dighton leave the options open, although I understand that the American ending was changed accordingly, which is a real shame but it was not uncommon then for such cultural vandalism to take place.

There is a Criterion DVD, which appears to be no longer available, which has the American ending, and a documentary called 'Made in Ealing', which I have in poor quality as I recorded it off the TV when it was first shown in the 1980s, so I will keep an eye out for it if it becomes available again.

There has been renewed interest in the film, and book, in the 21st century; Simon Heffer has done much to publicise the book, and amongst numerous articles there is, in the BFI Film Classics series, Michael Newton's slim volume on the film (see right) which is a mine of information.

2019 saw the 70th anniversary of the film's release, so there are new DVD/Blu-Ray releases; the book itself is still quite pricey though, it can be picked up new or from abebooks from around £12-£15.