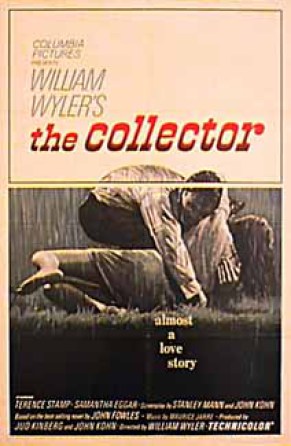

THE COLLECTOR (1965)

From the novel by John Fowles published in 1963

'The Collector' was John Fowles' first novel, published in 1963. Whilst much better known than many of the other books in this section of the website (usually little-read books made into famous films) I still think it should be better known and wider read than it is. The story, set out in stark terms, is very simple: Frederick (not Ferdinand, as I have seen in some places on the internet, this is a joke he plays on Miranda at one point) Clegg, a loner/loser, is a bank clerk somewhere not far from London (Tring is mentioned at one point) who lives with his Aunt Annie and her daughter Mabel, until he wins £73,000 on the pools (well over a million in today's money, maybe as much as £3 million). Whilst Annie and Mabel take themselves off to Australia on a trip to see family (and in fact never return) Clegg buys a remote country house near Lewes in Sussex, about an hour's drive from London, where he then hatches his plan...

...which is to kidnap a 20 year old art student, Miranda Grey, whom he has been admiring/stalking for some time, take her back to the country house, and hope that she will come to love him. He gets the cellar fitted out as a room, makes all the arrangements needed to make sure she won't be able to escape, and then kidnaps her in early-mid October. The rest of the story is that of their relationship, which ends with her death, presumably from some form of pneumonia after catching a cold from him, about two months later. He considers killing himself, but then, some three weeks after Miranda's death, is considering kidnapping another girl that he has seen, who looks like Miranda, and works at the sweets counter in Woolworths.

Laid out in those terms, it sounds like it might be a kind of crime thriller, but it is Fowles' narrative methods that are so intriguing. The first part of the book is written in the first person, from Clegg's perspective. This section, just under half the book, ends as Miranda's cold starts getting worse, and Clegg explains:

What I am trying to say is that it all came unexpected. I know what I did next day was a mistake, but up to that day I thought I was acting for the best and within my rights.

The second part of the book however is from Miranda's viewpoint, in the form of her diary. It is headed 'Oct 14th?' and starts off by stating it is the seventh night. She writes in her diary every day, unless there is a good reason why she has misssed a day, or several days. This section ends with her being too ill to write, the final entry being:

Oh God oh God do not let me die.

God do not let me die.

Do not let me die.

The book then ends by returning to Clegg's first person narrative, explaining from his viewpoint how it could be that he lets Miranda die, and then with a coda, as mentioned above, where he is considering another victim.

Whilst the film is quite faithful to the book (very much so in some of the minor details), of neccesity it has to lose all of Miranda's story to focus on the psychological struggle between the two main protagonists.

The film is almost entirely a two-hander, with Terence Stamp playing Frederick Clegg and Samantha Eggar playing Miranda Grey. The only other credited actors are Mona Washbourne, who plays Aunt Annie in a brief flashback, and Maurice Dallimore, who plays Clegg's nearest neighbour in possibly the only misjudged scene in the whole film and one that is not in the book. It is the concentration on the two of them - prisoner and warder, as Miranda describes it at one point - that suggests the source material was a play, not a novel, but there is some interesting background to the production of the film.

In the book, Miranda's diary is a mixture of putting her thoughts down about the fluctuating relationship between her and her captor, whom she nicknames Caliban, after the character in Shakespeare's play 'The Tempest', and thinking about her own life and some of the people in it, particuarly a character she constantly refers to as 'G.P.', a much older man than her who, as an artist in his own right, comes to act as her father/mentor figure. She describes the conflicting thoughts she has with regard to this Svengali figure, and towards the end she feels that she wants to go to him the moment she is let out/escapes. One of her last lucid comments before her fatal illness is:

I lay in bed last night and thought of G.P. I thought of being in bed with him. I wanted to be in bed with him. I wanted the marvellous, the fantastic ordinariness of him.

Although none of this features in the film of course, I was not aware that the director and producer did try to put some of this in, with Kenneth More featuring in a 35 minute section, described on wikipedia as a 'prologue', where he presumably played G.P. (although he would have been horribly miscast, as he neither physically resembles G.P. as described by Miranda, nor would his persona even remotely fit G.P.'s). In an interview with Samantha Eggar in the website Terror Trap in July 2014 (www.terrortrap.com/interview/samanthaeggar) she confirmed that:

"She's an art student and she has an affair with the character played by Kenneth. And she's in the middle of the affair...You see the back of Kenny's head amd me sitting there and suddenly sort of lowering my head because he's saying to me that he can't see my anymore."

Having read about More's part in the film, which was cut out completely, I can see that it's him sitting in the pub. Here's the full clip where Miranda is kidnapped:

The title of the book and film refers to Clegg's hobby of entomology, specifically butterflies, and the film opens with him catching one and placing it in his unpleasantly-named killing bottle. The symbolism is obvious; when Clegg shows Miranda around the house for the first time (see image above) he comments:

I was proud to be able to tell her something. She had never heard of aberrations.

'They're beautiful. But sad.'

Everything's sad if you make it so, I said.

'But it's you who make it so!' She was staring at me across the drawer. 'How many butterflies have you killed?'

You can see.

'No, I can't. I'm thinking of all the butterflies that would have come from these if you'd let them live. I'm thinking of all the living beauty you've ended.'

About a week after her imprisonment, Miranda writes:

I know what I am to him. A butterfly he has always wanted to catch. I remember (the very first time I met him) G.P. saying that collectors were the worst animals of all. He meant art-collectors, of course. I didn't really understand, I thought he was just trying to shock Caroline - and me. But of course, he is right. They''re anti-life, anti-art, anti-everything.

Here is how the scene is played out in the film:

The opposition between the two main characters, and how they view the world, is most explicit in the novel, as the format lends itself much more easily to exposition and a character's inner mind. Clegg views the world almost entirely in terms of class; he frequently refers to people with 'la-di-da' voices, and being unable to fit in with Miranda's 'clever' friends, and so on. Even after Miranda is dead, and his attention has moved on to another girl, Marian, who works in Woolworths, he thinks to himself:

She isn't as pretty as Miranda, of course, in fact she's only an ordinary common shop-girl, but that was my mistake before, aiming too high, I ought to have seen that I could never get what I wanted from Miranda, with all her la-di-da ideas and clever tricks. I ought to have got someone who would respect me more. Someone I could teach.

Miranda, in contrast, looks at the world in terms of art, and feeling. She despises and fears the New People (which I take to mean the new middle classes, the products of the 1944 Education Act) and sees herself as one of the Few, the artists who live and feel life.

It's a battle between Caliban and myself. He is the New People and I am the Few.

If this sounds corny and pretentious, that's because it is. Although she certainly does not deserve her terrible fate, she reveals herself through her diaries as an interminably fey and insufferably high-minded young aesthete. Like Holden Caulfield in 'Catcher in the Rye', a book she much admires and persuades Clegg to read, with predictably less than impressive results, she has a professed hatred of anything 'phoney', whilst being unable to see through her own shallowness and the self-indulgent nonsense and pomposity of G.P. (whose real name is George Paston; she later asks Clegg to buy her a painting a drawing by him) and their crowd. it is deliberately ironic that whilst Clegg believes he can teach Miranda to love him, she, in spite of herself, tries to teach Clegg about books, about art, about beauty.

For me one of the most telling moments is when she writes in her diary about her reaction to reading 'Saturday Night and Sunday Morning' by Alan Sillitoe:

I've just finished Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. It's shocked me. it's shocked me in itself and it's shocked me because of where I am...it must be wonderful to write like Alan Sillitoe. Real, unphoney. Saying what you mean...But it isn't enough to write well (I mean choose the right words and so on) to be a good writer. Because I think Saturday Night and Sunday Morning is disgusting. I think Arthur Seaton is disgusting. And I think the most disgusting thing of all is that Alan Sillitoe doesn't show that he's disgusted by his young man...

It's the inwardness of such people [Arthur Seaton]. Their not caring what happens anywhere in the world. In life.

Their being-in-a-box.

The casting is interesting. Samantha Eggar is fine as Miranda, although most of her inner thoughts have been removed for the script, there is still plenty of opportunity for her to express her views during her interactions with Clegg. Terence Stamp however is surely miscast as Clegg (he's far too good looking for a start) but having said that, the way he holds himself, almost drawing himself up within his own body, is a fantastic physical performance which exudes sexual and social repression.

This comes to a head when Miranda decides that she will have to seduce him:

November 28th

I've come to a tremendous decision today.

I've imagined being in bed with him.

It's useless just kissing him. I've got to give him such a tremendous shock that he'll have to release me.

But two days later she writes:

November 30th

Oh God.

I've done something terrible.

I've got to put it down. Look at it.

It is so amazing. That I did it. That what happened happened. That he is what he is. That I am what I am. Things left like this.

Worse than ever before.

She goes on to describe what happened, but we have already had Clegg's version:

Well, suddenly she came to me, she took my hand in her two [she is still tied up at the wrist] and pulled me to the fire, I let her. When we were there she held out her hands, she had such a look, so I untied them. At once she came close and kissed me again, for which she had to stand on tiptoe almost.

Then she did something really shocking.

I could hardly believe my eyes., she stood back a step and unfastened her housecoat and she had nothing on beneath. She was stark......

....It was terrible, it made me feel sick and trembling, I wished I was on the other side of the world. It was worse than with the prostitute; I didn't respect her, but with Miranda I knew I couldn't stand the shame.

He tells her, falsely, that a doctor has told him that he can't have sex, but what is key is that he loses all respect for her, which in the end seals her fate. This loss of 'respect', a word which keeps recurring in both book and film, is more important to him than Miranda's escape attempts, the most memorable (and one which nearly succeeds) of which is where she manages to hit him over the head when he is off guard (with a blunt axe in the book, with a spade in the film) but he recovers and gets her into the cellar before she can get away. In her turn, she is afraid she has killed him and of course that if he dies she will simply starve to death in her prison. In the book these two events (the seduction and then Miranda's attack on Clegg) are not connected, and in fact the axe attack takes place over a week before the attempted seduction, which is when Miranda is at her wits' end; however in the film they follow on, as this clip shows:

The ending, as those of you who are reading this page should already know, is chilling and horrible. Miranda catches pnuemonia and dies, as Clegg prevaricates and delays getting a doctor (in fact he never gets one, although he is on the verge of getting one in both book and film). He finds her diary, (I found her diary which shows she never loved me, she only thought of herself and the other man all the time) which helps persuade him not to kill himself but to deal with the situation and plan what to do next. He describes it thus:

She is in the box I made, under the appletrees. It took me three days to dig the hole...

...The room's cleaned out now and good as new.

I shall put what she wrote and her hair up in the loft in the deed-box which will not be opened until my death, so I don't expect for forty or fifty years. I have not made up my mind about Marian (another M! I heard the supervisor call her name), this time it won't be love, it would just be for the interest of the thing and to compare them and also the other thing, which as I say I would like to go into in more detail and I could teach her how. And the clothes would fit. Of course I would make it clear from the start who's boss and what I would expect.

But it is still just an idea. I only put the stove down there today because the room needs drying out anyway.

The film version is equally cold, with Edina Ronay (uncredited) playing a nurse who is set to be Clegg's next victim:

Film and book are easily available, both for around £6-£7. I feel about The Collector in much the same way as the book and film of The Right Stuff, or The Remains of the Day; in the case of The Right Stuff I saw the film first, then read the book. I thought I wouldn't like the film so much after reading the book, but in fact I had even more admiration for the film version, as Tom Wolfe's brilliant account of the Mercury astronauts is such a difficult book to adapt, that once can only admire how well they did it. The same applies in a way to The Remains of the Day; although I read the book before seeing the film, they have again done a superb job in getting almost all of Ishiguro's subtle and compelling story onto the screen, and provided an alternative, visual rendering of the book, rather than tried to put the book straight onto the screen, as they did with Waterland, another of my favourite books but one where the film version, starring Jeremy Irons, is a complete mess.

All that, and I didn't even mention The Smiths using a still from the promotional material for the film for the cover of 'What Difference does it Make?', only to find that Stamp wouldn't give approval for them to use it. By the time he'd changed his mind, Morrissy had imitated the cover anyway.