THE 'SOCIAL PROBLEM' FILMS OF DEARDEN & RELPH

Basil Dearden is one of the most prolific of British directors, directing over 35 films between the mid-40s and 1970, dying in a car crash in 1971 at the age of 60. He started out at Ealing Studios, co-directing Will Hay comedies such as The Goose Steps Out and My Learned Friend, then moved on to films which could broadly be termed 'post-war adjustment' films such as Frieda, Cage of Gold, The Ship that Died of Shame and others, along with iconic films such as The Blue Lamp.

He teamed up with producer Michael Relph (1915 - 2004) early on at Ealing, and by the late 40s they were working almost exclusively together, with almost all of Dearden's films being produced by Relph. When they left Ealing after making Davy in 1957 (not a film I've seen, but very unusually they switched roles, Dearden producing and Relph directing) they moved on to make what have become known as their 'social problem' films, starting with Violent Playground in 1958.

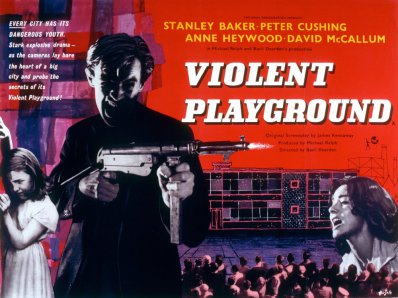

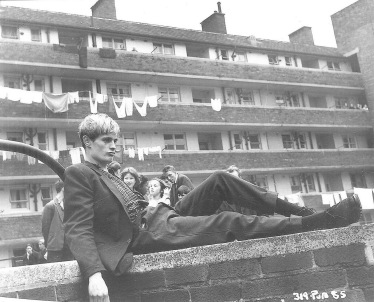

Violent Playground

This first film of its type looked at the then topical problem of 'juvenile delinquency' as it was known, no doubt influenced by US films such as The Blackboard Jungle and The Wild One. Stanley Baker stars as Sgt Truman, a tough copper in Liverpool who is, very much against his wishes, told to take over as the Juvenile Liaison Officer on his patch for a whie. Almost straightaway he has to take two young children back to their home, where he meets their sister Cathie (Anne Heywood). Whilst he becomes involved with Cathie he has his eye on another brother, Johnnie (was everybody in these films called Johnnie?) played by David McCallum, who seems to be the leader of a gang of thugs on the estate. In this well-known scene (it's been on youtube for years I think) Truman accompanies Johnnie back to his home, but finds Johnnie has a reputation to keep up:

Although this film aspires to social realism (for its time) Ken Loach it isn't; although it is set in, and filmed in, Liverpool, nobody has a Mersey/scouse accent and it owes more to the Dearden school of hard-won moral lessons of earlier films such as the 1952 Ealing production I Believe in You, about social workers.

As with so many Dearden/Relph films, the issue is wrapped up in a crime story, as Truman (before his transfer) and his colleagues had been trying to find out who is

responsible for a series of arson attacks in the city, known to them as 'Firefly'. However, unlike the latter Sapphire (see below) this doesn't detract from the social issue under

examination as it is blindingly obvious to eveyone, particularly us the audience, that Johnnie is behind it all. Finally he throws his natural caution to the wind by attacking a hotel where he

has been refused entry, thereby losing face in front of all his mates, only Truman has already worked this out and the police are on their way:

Johnnie ends up at his old school, only difference is he now has a machine gun and is holding the children hostage. What I love about this scene is that the police seem to have no rules whatsoever about how to organise a hostage scene, and although Johnnie has a machine gun the crowd that gather below the classroom are never dispersed by the police; even Peter Cushing, as the wise old priest, is allowed to go up a ladder to reason with him (given that he has started numerous serious fires in the city, just run over and killed one of his 'friends', got a machine gun and is holding a classroom of children hostage and is threatening to kill them, I would have thought that his reasoning days were over, but priests and other clergy in these films are eternally optimistic). However, he is pushed off it and injured so I hope he learnt some Health & Safety lessons from that little escapade...

All ends well - sort of - but overall, given the presence of Stanley Baker etc, this is a disappointing film which relies too heavily on platitudes, you know the kind of thing, 'the kids have got nowhere to play, what future are we building for them' etc etc. I personally blame rock 'n' roll for destoying their minds.

Sapphire

Much better is Sapphire (1959), a well-known film looking at the issue of race, wrapped up in a murder mystery story. Sapphire, a young woman, is found murdered on Hampstead Heath, and Supt Hazard (Nigel Patrick) and Insp Learoyd (Michael Craig) have to catch the killer. Things get complicated however when they realise that in fact she is not white, but black, but so light-skinned that she can pass for white. This brings into play a lot of cultural/social difficulties, and some of the language and assumptions prove slightly uncomfortable for most viewers these days, but the film's script does take care to show things in the round rather than just come up with platitudes about 'we can all live together happily if only'.

in this famous scene, the Plods go to a nightclub in search of one suspect, where they first hear the phrase 'lily-skins':

The line 'You can always tell - once they hear the beat of the bongo...' may sound crude to our ears, even offensive, but it's spoken by a black character. One of the persons spoken to during the investigation, a black ex-boyfriend of Sapphire's, clearly holds the police in contempt and pours scorn on them for their so-called liberal views. But my favourite scene on this point is the one between a friend of Sapphire's and their landlady, after the latter dismisses Sapphire's brother Dr Robbins (Earl Cameron):

Although the murder mystery is always to the fore - and unless you're like my Mum, who always knew immediately who did it, you'll be left guessing right to the last scene, as different suspects are offered up and then doubt cast upon their guilt - the film raises a number of points, as in the scene above, and I much prefer it as a film to Flame in the Streets, for example, and it has little of that preachiness which so often spoils these films, the odd exchange between Hazard and Learoyd aside. The team then moved on to another area of social injustice in their next film, the celebrated Victim.

Victim

Opinion is divided these days on the virtues of Victim, but I think it''s a brave film, with an outstanding performance from Dirk Bogarde as Melville Farr, who seems to have the world at this feet; a successful law practice, with a great chance of becoming a QC and a judge in time, with a beautiful wife (Sylvia Syms), a charming home, and probably a very nice dog or cat as well. Only thing is, Farr is homosexual (or at least bi-sexual). When 'Boy' Barrett (Peter McEnery) tries to contact Farr, the latter thinks Barrett is trying to blackmail him; in fact Barrett is himself being blackmailed and has stolen money from his workplace to try and pay the blackmailers. Although he is caught by the police, he hangs himself in his cell.

Farr, who had become involved with Barrett, decides to pursue the blackmailers, but gets precious little help from the others (including Dennis Price) who are being blackmailed, who simply pay up in order to avoid the exposure that would inevitably follow. Farr decides to make a stand, which he knows will ruin him, but is confronted by his wife Laura, who fears that Farr's old 'tendencies', which she knew about before but had hoped were a thing of the past, have resurfaced:

Dearden and Relph were much criticised for this film and Sapphire from the left, principally by critics from the journal Movie, who signalled Dearden out as the epitome of all that was safe and staid. This is grossly unfair - almost all of Dearden's films are at least watchable as entertainment - and certainly unfair in my view in terms of Victim, bearing in mind that at this time homosexuality was illegal and would remain so for several more years. The Wolfenden Report of 1957 had recommended decriminalising homosexuality for consenting adults, which basically is what the film argues for as well, but it is easily forgotten that Lord Wolfenden and his committe were hardly paragons of far-sighted liberal attitudes themselves, and I have seen interviews with Wolfenden in which he makes clear his repugnance at the very concept of homosexuality.

There is a strange 'sub-plot', set in a pub frequented by Barrett and many of his associates, whereby suspicion falls on two eavesdroppers, P.H. and Mickey, who appear to be the blackmailers; in this scene meanwhile the barman, Fred (Frank Pettit) gives his views on gays to a surprised Madge (Mavis Villiers):

There is something of a disappointment once the identity of the blackmailers is finally revealed, but then, unlike Sapphire, this was never the driving force behind the film, and as it ends Farr's future is unclear and there are certainly no easy answers.

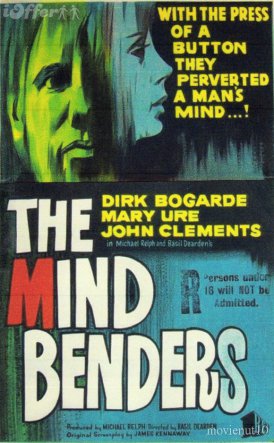

The Mindbenders

After All Night Long (which I've not seen), Life for Ruth (which I've written about in the 'Unsung films' section of this website), and A Place to Go, again which I've written about in relation to Rita Tushingham on this site, Dearden and Relph made the last of their uniquely British films with The Mind Benders.

This little-seen film doesn't really fall into the 'social problem' category but instead is usually regarded, when mentioned at all, as an 'interesting failure' which is probably fair enough. When Professor Sharpey, who is under surveillance by MI5 (or is it MI6? Can never remember which is which) kills himself, it appears that he was selling secrets to the Russians and he'll be marked down forever as a traitor. Major Hall (John Clements) finds out that the Professor was involved, with colleagues Longman (Dirk Bogarde) and Tate (Michael Bryant), in sensory deprivation experiments at Oxford University, and Longman is adamant that Sharpey's mind was twisted due to these experiments; "File him under Z for Zombie, not T for Traitor" he tells Hall.

Longman agrees to go back in the 'tank', where the experiments are conducted, but Hall (and a reluctant Tate) deliberately poison Longman's mind against his wife, Oonagh (Mary Ure), as part of the experiment...

Bogarde's character becomes extremely unpleasant, although to be honest he was pretty obnoxious before, as we the audience wait to see where it all lead...The answer is, unfortunately, nowhere in particular, and several questions are raised but then not answered properly. This scene though gives a flavour of the style of the film, as Longman prepares to go in the tank, for this ill-fated experiment:

It is hard to know what to make of it all, even in terms of this period of British cinema, which had taken on a wider range of subjects. The film did not do well at the box office, perhaps unsurprisingly, and Dearden and Relph moved on to more mid-Atlantic co-productions such as Khartoum and The Assassination Bureau; indeed it is noticeable that a book on Dearden - 'Liberal Directions: Basil Dearden and Postwar British Culture' edited by Alan Burton, Tim O'Sullivan and Paul Wells - misses out on all these films and the essay on The Mind Benders is followed by one on Dearden's last film, The Man who Haunted Himself, a return to form and Roger Moore's own favourite of his films. The Man who Haunted Himself does not quite fit in here, but I hope to write about it in the near future (March 2015) in the 'Unsung Films' section.

The pic at the top shows Relph (left) and Dearden (right) on the set of Victim.